What about Long COVID?

Long COVID is not a meaningful diagnosis. It’s an acknowledgement that something is wrong and COVID was probably the cause. The hodgepodge of generally accepted lasting symptoms includes:

- Breathing problems; and / or

- Fatigue and pain (e.g. headaches, muscle pain); and / or

- Lost mojo and mental dysfunction (e.g. brain fog, depression); and / or

- Vulnerability to other horrible things (e.g. stroke, diabetes).

Those symptoms may start during infection and stick around or they may appear later. Severity ranges from minor to existential. A bad case looks like:

“I seemed to be unable to recover and I was now suffering with a crippling fatigue as well as the other symptoms of exhaustion, a strange taste and brain fog. [...] I would now struggle to walk to the end of my street [...] I currently feel I am living in a ‘COVID’ cycle of symptoms (fever, cough and metallic taste), extreme fatigue and brain fog then a few days of normality. Slowly, after nearly six months I am slowly beginning to see more ‘normal’ days but as soon as I begin to feel better the cycle starts again.”

What is reliably known?

Very little.

One study says 75% of those infected are unwell 12 weeks later. One says 10%, later corrected to 2%. A bunch more cover every number in between.

That those numbers exist at all is remarkable while the pandemic is ongoing. But none of them are reliable1. You can play a good game and still lose.

Problems acknowledged, we can make some low confidence assumptions about questions that matter to us:

Can you develop Long COVID after a mild infection?

Yes. But most figures are wildly overstated2.

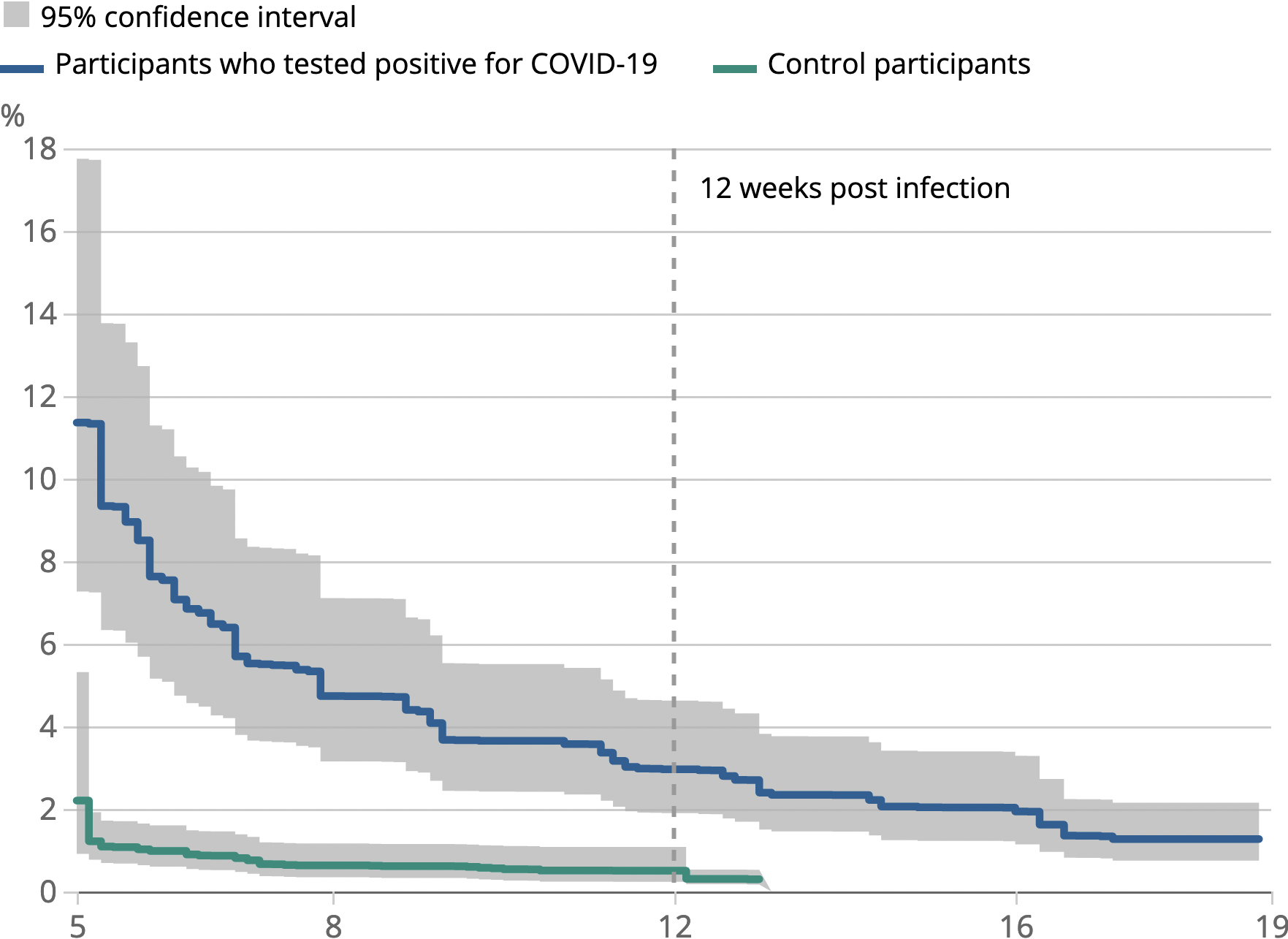

According to self-diagnoses on surveys 12% suffer from some form of Long COVID 12 weeks after a mild infection3.

When a doctor asks the questions, face-to-face with eyebrow raised judgementally, the number drops to 5%.

Then subtract all the people who have recognised symptoms but never had COVID and only 1–2% have any form of Long COVID symptoms 12 weeks after a mild case of COVID.

Can a mild infection lead to crippling Long COVID?

Probably. If so, rarely.

When asked “Does [Long COVID] reduce your ability to carry-out day-to-day activities compared with the time before you had COVID-19?” a fifth of respondents from the survey above said “yes, a lot.”

If those results reflect reality and they match your definition of ‘crippling’ then you face ~300:14 odds of being pretty much fine during infection but becoming severely ill at some point afterwards.

What affects the likelihood or severity of Long COVID?

The severity of your initial infection.

Post-infection symptoms are common after hospitalisation. For ICU admissions they’re practically inevitable and generally more severe5. The more severe the symptoms, the longer they tend to last.

Observations comparing people with similar initial infections but different Long COVID severity suggest women might be at slightly greater risk6. Youth and health might be vaguely protective. Nothing else jumps out.

Does it get better?

Yes, mostly. Slowly. Half of people ill at 12 weeks are still ill 2 months later.

But sometimes no. Graphs like the one above plateau rather than going to zero over time. Some people stay ill.

Some people’s lives have been destroyed and they have no idea what’s wrong with them or if they will ever get better.

Could COVID have as-yet-unknown, long-term consequences?

Very yes.

COVID is a black box. Millions of hospital cases under professional observation have revealed the short-term symptoms. How the disease causes those symptoms—which proteins affect what, where, and how—is educated guesswork.

Predicting long-term consequences from that wobbly vantage is a non-starter. Rigorous observations would help but they don’t exist. Surprises are probable. Some might be terrible.

There are rumours of lung scarring after even asymptomatic COVID; cardiovascular problems following mild COVID; and IQ loss for everyone. Mental health problems after COVID show up in most studies.

If any of that smoke turns out to be fire, bugger.

Assuming the worst might be a sensible response. Risk appetites differ. Mine insists that I at least try to make some low confidence guesses about unknowns based on the knowns:

Guess #1: Uniquely terrible consequences are unlikely.

COVID can and does have a devastating impact. Someone hospitalised with COVID, months later, is at increased risk of life-destroying secondary outcomes:

- 10x risk of clotting problems;

- 4x risk of heart problems;

- 7x risk of kidney problems;

- 4x risk of metabolic problems

But similar diseases are similarly devastating. Hospitalised pneumonia patients face identical risks post-infection. Other viruses have (uncommonly) resulted in lasting symptoms that are identical to some versions of Long COVID: brain fog, fatigue, pain, and weakness.

Case numbers might be uniquely terrible but the consequences have so far been run-of-the-mill terrible for a serious disease.

Guess #2: Any common and severe long-term effects would already be visible.

A misery that affects most people at X years will affect some people at Y months7.

If the misery is noteworthy and affects enough people it becomes visible, somehow8.

There have been tens of millions of infections in the UK alone. Anything serious enough for us to worry would probably have already affected enough people to make waves.

What does that mean for you?

Catching COVID is a double gamble.

The first is getting through infection. In January 2021 someone like you faced ~40:1 odds of hospitalisation.

The second is recovering without incident. Looking at the visible risks and holding tight to a grain of salt someone like you faced ~300:1 odds of disability following a mild infection.

Those odds will change as the virus changes and treatments become available. We cannot know the timeframe of those changes or the net direction.

For now, our best / only informed guess at current risk is recent risk.

According to that guess you recently had ~35:1 odds of an unacceptable outcome if you had caught COVID.

Further Reading

Many thousands of words of relevant-but-not-relevant-enough information were cut. This started with a bazillion research notes-to-self and links, then went through a round of chunking and cutting.

If I had to do this from scratch I’d start with:

- Coronavirus Infection Survey“Updated estimates of the prevalence of post-acute symptoms among people with coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK”

- REACT-1“Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community sample of 508,707 people” Case estimates, who’s affected and how.

- (Data from US Department of Veterans Affairs)“High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19”

- (Data from a bunch of US healthcare providers)“Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection”

And read these for context:

- @MaosBot on Twitter First-hand account of Long-COVID-as-life-destroying biblical-curse.

- Astral Codex TenLong COVID: Much More Than You Wanted To Know Good-faith, rigorous and critical summary of available data.

- ONS“How common is long COVID? That depends on how you measure it” A half-apology for a serious failure of data analysis (or why ‘data’ or ‘studies show...’ or ‘the science says’ are generally fluff.)

- OpenSAFELY“Rates of serious clinical outcomes in survivors of hospitalisation with COVID-19” Putting Long COVID in perspective re: another serious respiratory disease.